The Due Process Provisions of the 2020 Title IX Regulations Were Successful. We Should Fight to Keep Them.

Jonathan Taylor, Founder, Title IX for All

March 1, 2024

The Title IX regulations that went into effect in August of 2020 were critically necessary. Before their implementation, schools too often punished and expelled students accused of misconduct (sexual harassment, assault, stalking, and so forth) in what were little more than sham proceedings. Wrongly punished students found their education prospects shattered, their careers derailed, and their reputations destroyed. Some students were punished despite not being found responsible for any misconduct. Some even committed suicide.

Among other provisions, the 2020 regulations required schools to provide accused students with meaningful notice of the accusation, meaningful access to evidence, and a meaningful opportunity to respond to the evidence. Those critical protections are now threatened by a regulatory rewrite spearheaded by the Biden administration.

The U.S. Office of Management and Budget is currently accepting meetings from the public regarding this rewrite. Advocates and concerned citizens should consider this an opportunity to make their voices heard and to push back on attempts by the Biden administration to roll back due process. To do this, it may help to draw attention to indicators that the regulations have been successful. Below are several arguments that the due process protections have been successful and should remain.

1. Trends in Lawsuits by Accused Students Reflect the Need for Due Process

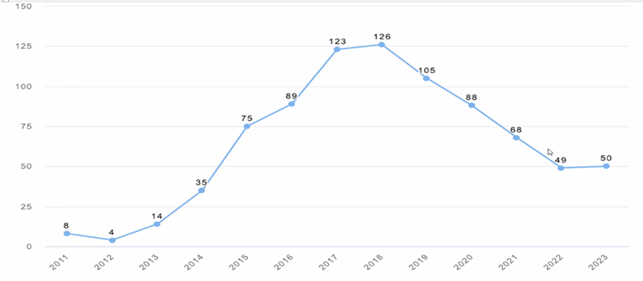

The graph above shows the trend in annual filings of lawsuits by students accused of Title IX violations in state and federal courts since 2011.[1] This trend is highly consistent with changes to Title IX guidance and regulation. Simply put, the fewer the rights afforded accused students and the weaker the emphasis on due process by the current presidential administration, the more lawsuits by accused students we see. The reverse is also true.

In 2011, the Department of Education issued guidance (the “Dear Colleague” letter) for schools to investigate Title IX complaints more rigorously. The Department also threatened to revoke funding from schools that failed to comply and initiated highly visible investigations that named and shamed many of them. Afraid of lawsuits, federal investigations, and bad press, schools rushed to comply – and soon overcorrected. As you can see in the graph, that overcorrection was the genesis of the litigation movement for accused students. Lawsuits trickled in at first, gained a foothold in 2014 and 2015, and then spiked, reaching their peak in 2017 and 2018.

In September 2017, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos rescinded the Department of Education’s 2011 guidance letter and announced an imminent rulemaking process to further flesh out schools’ liabilities and the balance of rights between complainants and respondents in school grievance procedures. The Department issued a draft of the new regulations in November 2018 and published the final rule in May 2020. The rule went into effect on August 14, 2020.

DeVos’ rescinding the Dear Colleague letter and announcing a new rulemaking procedure made it clear that the era of federal complicity (if not encouragement) for schools to systematically railroad accused students was over. Consistent with this new era of due process, annual filings of lawsuits have declined by twenty or more since 2018. By 2023, lawsuits had declined by sixty percent from their peak: from 126 in 2018 to around 50 in 2013. This indicates that the regulations are having the intended effect: despite troublesome hotspots remaining, schools have, in many cases, made efforts to comply.

The decline stopped in 2022, however. That is no accident; it occurred a year after the Biden administration announced a plan to undo much of the due process protections afforded by the 2020 regulations. While 2024 has just begun, at least seven lawsuits have been filed by accused students as of mid-February. If recent trends continue, we will likely see at least as many lawsuits in 2024 as we did in 2023 – and likely more.

2. The 2020 Regulations Have Consistently Withstood Legal Challenges

Five legal challenges have been made against the regulations in federal court. All have failed to overturn them. While two failed simply because the plaintiffs lacked standing, others failed on the merits of their claims. The five lawsuits are:

- Victim Rights Law Center v. DeVos

This lawsuit failed to overturn the 2020 regulations by arguing it was in violation of the Administrative Procedures Act and discriminates against women. It was, however, successful in overturning a narrow provision[2] that required schools to not rely on statements that were not subject to cross-examination when making their determinations.

2. The Women’s Student Union v. U.S. Department of Education

This case was initially dismissed for lack of standing. WSU – a feminist student association – argued the 2020 regulations would “frustrate its mission” to assist complainants. The court held otherwise: that such a group “may not establish injury by engaging in activities that it would normally pursue as part of its organizational mission. WSU appealed the dismissal to the Ninth Circuit which then stayed the case pending the completion of the Biden administration’s rulemaking process.

3. State of New York v. U.S. Department of Education

Brought by the New York Attorney General’s office, this lawsuit sought an injunction to prevent the rule from going into effect. It failed on every factor upon which injunctive relief is decided: the likelihood they would succeed on the merits of their claims, whether they or students would suffer irreparable harm, the balance of equities (“harms”) between the parties if the injunction did or did not go into effect, and the public interest. The State of New York then withdrew the lawsuit.

4. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. DeVos

A coalition of state Attorneys General brought this lawsuit to postpone the effective date of the rule, declare it unlawful, vacate it, or enjoin the Department of Education from applying and enforcing it. The motion to postpone the rule failed. The rest of the proceedings have been stayed.

5. Know Your IX et al v. DeVos

Similar to the WSU case, Know Your IX and similar organizations argued that the 2020 rule “frustrates its mission” to assist and advocate for complainants in Title IX proceedings. Judge Bennett disagreed and dismissed the case.

3. Schools Have Continuously Exhibited a Desire to Deny Due Process

The due process protections provided by the 2020 Title IX rule had one “clever workaround” for schools: they did not apply to allegations of misconduct occurring off-campus and outside an educational program or activity.[3] Schools could, however, still investigate and punish students under a “non-Title IX” policy that lacked those protections.

Advocates for complainants believed that schools would use this as an excuse to forgo investigating such alleged misconduct at all since there was now no federal requirement to do so. The reality, however, is that Title IX bureaucracy tends to be staffed by what some have called the “sex police”: bureaucrats who regard it as their mission to root out any kind of potentially offensive behavior and continuously seek reasons to expand their reach rather than retract it. Lawsuits by accused students have shown this is the case. Starting in 2021, they brought a new batch of lawsuits arguing schools were erroneously applying “non-Title IX” policies[4] as an excuse to railroad them out of campus.

The Biden administration seeks to expand the requirements of Title IX so that schools must investigate off-campus activity but without the due process protections that would curb some of the worst impulses of the sex police.

4. The 2020 Regulations Have Forced Their Opponents to Inadvertently Defend Them

Opponents of due process often argue that such protections would make school grievance procedures “too quasi-judicial” or “too court-like.” This argument is not sincere, as such groups have demanded that courts and schools recognize and treat grievance procedures as quasi-judicial and court-like when it benefits accusers.

While many examples of this exist, perhaps the most blatant recent example comes from the lawsuit Khan v. Yale in which an accused student also sued his accuser Jane Doe for defamation. Jane Doe argued that even if her statements against Khan were deliberately false and malicious, she was nonetheless entitled to immunity from a defamation lawsuit because her statements were made in the context of a quasi-judicial proceeding. In 2022, fifteen powerful advocacy groups filed an amicus brief supporting Doe’s argument – including those who opposed the 2020 regulations for being too quasi-judicial.

But as Connecticut Supreme Court held, Yale’s investigation and punishment of Khan occurred before the 2020 regulations went into effect and hence lacked virtually all the key safeguards that would establish the proceedings as quasi-judicial and entitle Jane Doe to immunity.

Other Arguments and Conclusion

Although there are numerous indicators that the 2020 regulations have been successful, these are four particularly noteworthy ones. Other potential supporting arguments could be that:

- Litigation costs for universities will skyrocket if accused students are again routinely railroaded off campus, and that

- The due process protections of the 2020 regulations have disincentivized false reporting and sham proceedings, which in turn bolsters the integrity of Title IX grievance procedures and allows school resources to be distributed more effectively.

Advocacy opportunities are often time sensitive; once they are gone, they are gone. This advocacy window is still open. Please go to the Office for Management and Budget website and register a meeting to make your voice heard.

Links:

[1] See the Title IX Lawsuits Database for a full listing of these lawsuits.

[4] Examples include Doe v. Rutgers and Doe I v. SUNY-Buffalo.